I climb into my tent on Hawk Mountain, Georgia, and a sense of smugness comes over me. It’s the first night on the Appalachian Trail and I am feeling confident. I’ve hiked farther and faster than everyone around me that day. Having completed several multi-week backpacking trips before, including 400 miles of the AT, I know that I am more experienced and better prepared than these newbies.

“I passed many people today, but nobody passed me” I thought. As someone who has never been particularly athletic or competitive, it was satisfying to feel a sense superiority in my physical abilities. For the next few days, I continued to whiz by other hikers, my ego growing each time. “I am going to finish this hike in no time.”

Then it happened: someone passed me. Then more people passed me. Within a few short weeks, everyone was passing me. The newbies had started to find their trail legs and gain speed. My over-inflated ego began to deflate quickly.

In the Smokies, I started hiking with a tramily. At first, we were all roughly the same pace, but over the next 1000 miles, I watched them all get stronger and faster while I seemed to be stuck at the same pace. Somewhere in the middle of Pennsylvania, I got behind. I couldn’t keep up with their pace anymore. I had to swallow my pride and let them go.

I started the hike believing I was fast, but every time someone else outpaced me, it challenged that belief. This happened over and over again, slowly chipping away at me, until my belief had completely flipped. I realized I was actually quite slow.

This bothered me to no end. I was doing everything right! An experienced hiker like me should be able to move faster than this!

I don’t know why I felt like I had something to prove. Literally no one except me cared how quickly I finished the AT. The point of my thru-hike was not speed. It was not a race, but it felt like one. I spent an embarrassing amount of mental energy obsessing about my pace. Why couldn’t I hike as fast as everyone else? Was it may age? gender? body mechanics? feet? was there a medical reason? did I just need to try harder?

Then I remembered, I am a tortoise.

You recall the story of the tortoise and the hare. The tortoise and the hare decide to have a race. The hare is much faster, but being overly confident, takes a nap during the race, allowing the slow and steady tortoise to win.

This story has always resonated with me. I tend to adopt a slow, steady, and patient approach to achieving goals or facing challenges. I believe in persistence and consistency. Time after time in my life, I have found success not through bravado or sudden bursts of inspiration, but through slow, consistent effort and determination.

As a music student, I did not have the pure raw talent that I saw in some of my peers. I was not a child prodigy, I did not have perfect pitch, and I couldn’t learn a concerto by ear.

I got good the boring way, by practicing. I’d religiously wake up early before my classmates to work on fundamentals. I practiced every day for three to four hours, hardly ever missing a day.

No individual practice session was groundbreaking; progress happened very slowly, almost imperceptibly, in the consistency of the daily grind. The hard work paid off and I began winning competitions and auditions. By the time I graduated, I was the best horn player in the music school, not because I was the most talented, but because I had stayed the course, unwavering in my commitment to slow and steady progress.

Before joining the Army, I couldn’t do a single push up and I had never run farther than a mile. I had never fired a gun. Now after 13 years time in service, I’ve done quite well in the military, but not because I have some special ability. Trust me, I’m no military genius. I simply show up at the right time, in the right place, in the right uniform, day after day after day after day. With time, the compounding effect of tiny daily investments leads to big results.

I am a tortoise. I don’t know why I thought it would be any different with thru-hiking.

Being a tortoise is hard work and it can be boring. Maybe after years of tortoise-like grit, I wanted something that I was just effortlessly good at.

Like the hare, I jumped out of the gate swiftly and confidently. Also like the hare, I got tired. I pushed harder than my body wanted to and I suffered the consequences. My body ached and I developed a limp. My feet felt like they were filled with poison, burning with every step. Every day I collapsed with fatigue and frustration. Being a hare did not work for me. That is not who I am.

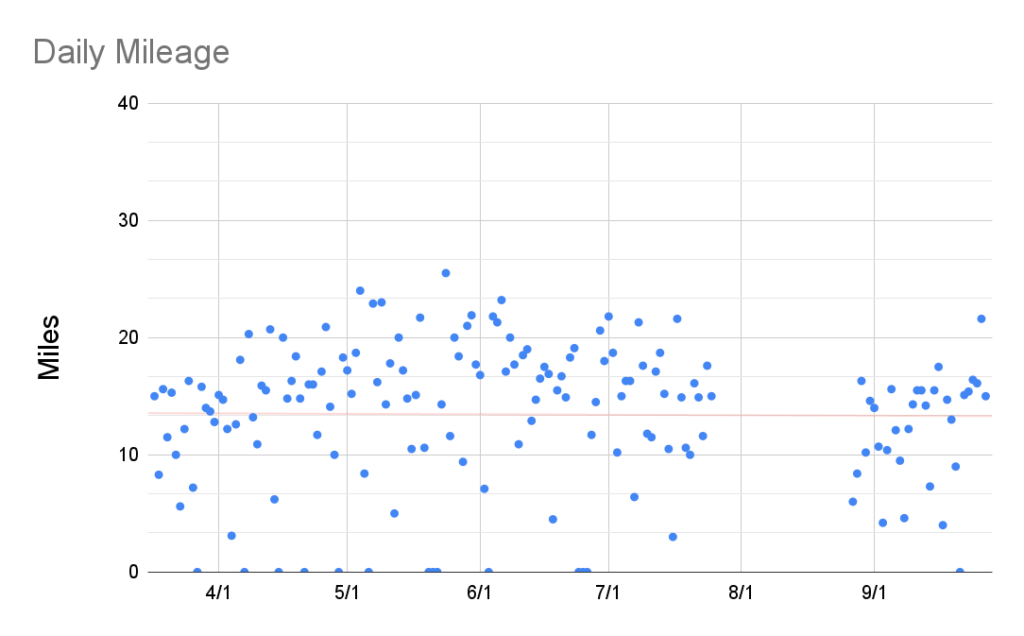

Thinking about the tortoise, I began to change my strategy. I was hiking alone now so I was free to set my own pace. I set more modest mileage goals for each day and tried to not worry about hiking fast. With the shorter days, I became less fatigued. Though the mileage on any particular day was never impressive, I found that it was a much more sustainable strategy. My feet felt better. I didn’t need as many rest days. In fact, I stopped taking zeros completely. In the final two months of my hike, I only took one zero, which was due to weather.

I wasn’t opposed to taking rest if I needed it. Generally speaking, rest and recovery are imperative components of physical activity, but in this case my body just didn’t want days off. It seemed happier hiking every day, even if just a few miles. Previously I would feel stiff and lethargic after a day off. When I started walking at least a little bit every day, I was able to remain agile while also gaining a feeling of momentum.

In the last quarter of the hike, I started to notice something: I was going the same pace as everyone else. Not on hourly basis, or even a daily one, but in the long term. Someone would zoom by me and I think “Well, I’ll never see them again.” Then four or five days later, I’d saunter up to a town to resupply, and there they were, taking a day off. This happened repeatedly. In Vermont, I even almost caught up to the tramily I had fallen behind back in Pennsylvania. I couldn’t believe it when I discovered I was only 20 miles behind them. Because I had to pause my hike for several weeks due to a family emergency, I wasn’t able to catch them, but I think I might have otherwise.

I’m not the only one who finds success in the tortoise strategy. In 2011, Jennifer Phar Davis set the record for the fastest known time on the AT (for both women AND men), completing the entire 2200 miles in just 46 days. In her book The Pursuit of Endurance, she writes:

“One of my goals in life is to not try to outmuscle or outpace those around me, but to keep my head down and focus on what I’m doing so that I can do it well. In school, sports, and my work I have a history of being boringly good. It’s not sexy, but it’s effective. On the record [hike of the AT], I believed that consistent output over a prolonged period would be more efficient than short bursts of speed followed by lengthier rests.”

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

While Jennifer Phar Davis’s tortoiseness led her to set the all-time record for hiking the AT — literally winning the race — my results were…. average. According to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, the average time to complete a thru-hike is “a week or two shy of six months.” My total time? Two weeks shy of six months. That is, perfectly average.

I am ok with average. For all the days I spent stressing about my pace, feeling like the slowest one out there, I was actually doing just fine. I just had to figure out how to do it my way. (I also take solace in the fact that only 25% of prospective thru-hikers even make it to the end, so just by finishing, I am in fact above average after all — phew!).

Like real life, a thru-hike is more about personal growth and savoring the journey, rather than reaching the end goal as quickly as possible. Imagine trying to race through your life as quickly as possible to reach the end. It makes no sense!

Life is about finding a rhythm that suits your personal strengths and abilities. It is liberating and empowering when you finally stop comparing yourself to others, and instead focus on actualizing your own potential.

Absolute favorite blog post yet. <<<<>>>>

I find this in plant medicine journeys too. I (and others, I see over and over) go in expecting to leap forward, to become someone else, to discover they were someone else all along, or unlock a new achievement level. Just to (eventually) come to with clarity that they are exactly who they are, and always have been. Maybe some layers of ego have been shed, but that process is typically humbling (or even humiliating) rather than enlightening. To accept our own nature with grace: our strengths, our weaknesses, our unique ways of moving, thinking, & being. To accept and then decide, “now what do I want to do?”

Thanks for sharing your insights! That’s a powerful question, “now what do I want to do?” Good food for thought.

I love this post! Some of life’s most valuable lessons are shared here. We all need to remember how to succeed at our own pace. You have accomplished far more than 2200 miles on foot by doing and sharing your experience with us. Thank you!

Thanks for reading along as I process my lessons learned! Glad you’re enjoying it